Maryland

Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Pagetype/setindex' not found. Lua error in Module:Effective_protection_level at line 52: attempt to index field 'TitleBlacklist' (a nil value).

[[Category:Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Pagetype/setindex' not found. with short description]]

[[Category:Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Pagetype/setindex' not found. with short description]]

Maryland | |

|---|---|

| State of Maryland | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): "Fatti maschii, parole femine" (English: "Strong Deeds, Gentle Words")[3] The Latin text encircling the seal: Scuto bonæ voluntatis tuæ coronasti nos ("With Favor Wilt Thou Compass Us as with a Shield") Psalm 5:12[4] | |

| Anthem: None ("Maryland, My Maryland" repealed) | |

Map of the United States with Maryland highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of Maryland |

| Admitted to the Union | April 28, 1788 (7th) |

| Capital | Annapolis |

| Largest city | Baltimore |

| Largest metro | Baltimore–Washington Metro Area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Larry Hogan (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Boyd Rutherford (R) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Delegates |

| Judiciary | Maryland Court of Appeals |

| U.S. senators | Ben Cardin (D) Chris Van Hollen (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 7 Democrats 1 Republican (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12,407 sq mi (32,133 km2) |

| • Land | 9,776 sq mi (25,314 km2) |

| • Water | 2,633 sq mi (6,819 km2) 21% |

| • Rank | 42nd |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 119 mi (192 km) |

| • Width | 196 mi (315 km) |

| Elevation | 350 ft (110 m) |

| Highest elevation | 3,360 ft (1,024 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2020[8]) | |

| • Total | 6,185,278 |

| • Rank | 19th |

| • Density | 619/sq mi (238/km2) |

| • Rank | 5th |

| • Median household income | $80,776 (2,017)[7] |

| • Income rank | 2nd |

| Demonym(s) | Marylander |

| Language | |

| • Official language | None (English, de facto) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | MD |

| ISO 3166 code | US-MD |

| Traditional abbreviation | Md. |

| Latitude | 37° 53′ N to 39° 43′ N |

| Longitude | 75° 03′ W to 79° 29′ W |

| Website | www |

| Maryland state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Baltimore oriole |

| Butterfly | Baltimore checkerspot butterfly |

| Crustacean | Blue crab |

| Fish | Rock fish |

| Flower | Black-eyed Susan |

| Insect | Baltimore checkerspot |

| Mammal | Calico cat Chesapeake Bay Retriever Thoroughbred horse |

| Reptile | Diamondback terrapin |

| Tree | White oak |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Milk |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Dinosaur | Astrodon johnstoni |

| Food | Blue crab Smith Island Cake |

| Fossil | Ecphora gardnerae gardnerae |

| Gemstone | Patuxent River stone |

| Mineral | Agate |

| Poem | "Maryland, My Maryland" by James Ryder Randall (1861, adopted 1939, repealed 2021) |

| Slogan | Maryland of Opportunity |

| Sport | Jousting Lacrosse |

| State route marker | |

| State quarter | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Maryland (US: /ˈmɛrələnd/ (listen) MERR-ə-lənd)[lower-alpha 1] is a state in the Mid-Atlantic[10] region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. Baltimore[11] is the largest city in the state and the capital is Annapolis. Among its occasional nicknames are Old Line State, the Free State, and the Chesapeake Bay State. It is named after the English Queen Henrietta Maria, known in England as Queen Mary, who was the wife of King Charles I.[12][13]

Sixteen of Maryland's twenty-three counties, as well as the city of Baltimore, border the tidal waters of the Chesapeake Bay estuary and its many tributaries,[14][11] which combined total more than 4,000 miles of shoreline. Although one of the smallest states in the U.S., it features a variety of climates and topographical features that have earned it the moniker of America in Miniature.[15] In a similar vein, Maryland's geography, culture, and history combine elements of the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, and Southern regions of the country.

Before its coastline was explored by Europeans in the 16th century, Maryland was inhabited by several groups of Native Americans - mostly by the Algonquin, and to a lesser degree by the Iroquois and Sioux.[16] As one of the original Thirteen Colonies of England, Maryland was founded by George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore, a Catholic convert[17][18] who sought to provide a religious haven for Catholics persecuted in England.[19] In 1632, Charles I of England granted Lord Baltimore a colonial charter, naming the colony after his wife, Queen Mary (Henrietta Maria of France).[20] Unlike the Pilgrims and Puritans, who rejected Catholicism in their settlements, Lord Baltimore envisioned a colony where people of different religious sects would coexist under the principle of toleration.[19] Accordingly, in 1649 the Maryland General Assembly passed an Act Concerning Religion, which enshrined this principle by penalizing anyone who "reproached" a fellow Marylander based on religious affiliation.[21] Nevertheless, religious strife was common in the early years, and Catholics remained a minority, albeit in greater numbers than in any other English colony.

Maryland's early settlements and population centers clustered around rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Its economy was heavily plantation-based and centered mostly on the cultivation of tobacco. Britain's need for cheap labor led to a rapid expansion of indentured servants, penal labor, and African slaves. In 1760, Maryland's current boundaries took form following the settlement of a long-running border dispute with Pennsylvania. Maryland was an active participant in the events leading up to the American Revolution, and by 1776, its delegates signed the Declaration of Independence. Many of its citizens subsequently played key political and military roles in the war. In 1790, the state ceded land for the establishment of the U.S. capital of Washington, D.C.

Although then a slave state, Maryland remained in the Union during the American Civil War, its strategic location giving it a significant role in the conflict. After the war, Maryland took part in the Industrial Revolution, driven by its seaports, railroad networks, and mass immigration from Europe. Since the Second World War, the state's population has grown rapidly, to approximately six million residents, and it is among the most densely populated U.S. states. As of 2015[update], Maryland had the highest median household income of any state, owing in large part to its proximity to Washington, D.C. and a highly diversified economy spanning manufacturing, services, higher education, and biotechnology.[22] The state's central role in U.S. history is reflected by its hosting of some of the highest numbers of historic landmarks per capita.

Geography

Maryland has an area of 12,406.68 square miles (32,133.2 km2) and is comparable in overall area with Belgium [11,787 square miles (30,530 km2)].[23] It is the 42nd largest and 9th smallest state and is closest in size to the state of Hawaii [10,930.98 square miles (28,311.1 km2)], the next smallest state. The next larger state, its neighbor West Virginia, is almost twice the size of Maryland [24,229.76 square miles (62,754.8 km2)].

Description

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

Maryland possesses a variety of topography within its borders, contributing to its nickname America in Miniature. It ranges from sandy dunes dotted with seagrass in the east, to low marshlands teeming with wildlife and large bald cypress near the Chesapeake Bay, to gently rolling hills of oak forests in the Piedmont Region, and pine groves in the Maryland mountains to the west.

Maryland is bounded on its north by Pennsylvania, on its west by West Virginia, on its east by Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean, and on its south, across the Potomac River, by West Virginia and Virginia. The mid-portion of this border is interrupted by District of Columbia, which sits on land that was originally part of Montgomery and Prince George's counties and including the town of Georgetown, Maryland. This land was ceded to the United States Federal Government in 1790 to form the District of Columbia. (The Commonwealth of Virginia gave land south of the Potomac, including the town of Alexandria, Virginia; however, Virginia retroceded its portion in 1846). The Chesapeake Bay nearly bisects the state and the counties east of the bay are known collectively as the Eastern Shore.

Most of the state's waterways are part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, with the exceptions of a tiny portion of extreme western Garrett County (drained by the Youghiogheny River as part of the watershed of the Mississippi River), the eastern half of Worcester County (which drains into Maryland's Atlantic coastal bays), and a small portion of the state's northeast corner (which drains into the Delaware River watershed). So prominent is the Chesapeake in Maryland's geography and economic life that there has been periodic agitation to change the state's official nickname to the "Bay State", a nickname that has been used by Massachusetts for decades.

The highest point in Maryland, with an elevation of 3,360 feet (1,020 m), is Hoye Crest on Backbone Mountain, in the southwest corner of Garrett County, near the border with West Virginia, and near the headwaters of the North Branch of the Potomac River. Close to the small town of Hancock, in western Maryland, about two-thirds of the way across the state, less than 2 miles (3.2 km) separates its borders,[24] the Mason–Dixon line to the north, and the northwards-arching Potomac River to the south.

Portions of Maryland are included in various official and unofficial geographic regions. For example, the Delmarva Peninsula is composed of the Eastern Shore counties of Maryland, the entire state of Delaware, and the two counties that make up the Eastern Shore of Virginia, whereas the westernmost counties of Maryland are considered part of Appalachia. Much of the Baltimore–Washington corridor lies just south of the Piedmont in the Coastal Plain,[25] though it straddles the border between the two regions.

Geology

Earthquakes in Maryland are infrequent and small due to the state's distance from seismic/earthquake zones.[26][27] The M5.8 Virginia earthquake in 2011 was felt moderately throughout Maryland. Buildings in the state are not well-designed for earthquakes and can suffer damage easily.[28]

Maryland has no natural lakes, mostly due to the lack of glacial history in the area.[29] All lakes in the state today were constructed, mostly via dams.[30] Buckel's Bog is believed by geologists to have been a remnant of a former natural lake.[31]

Maryland has shale formations containing natural gas, where fracking is theoretically possible.[32]

Flora

As is typical of states on the East Coast, Maryland's plant life is abundant and healthy. A modest volume of annual precipitation helps to support many types of plants, including seagrass and various reeds at the smaller end of the spectrum to the gigantic Wye Oak, a huge example of white oak, the state tree, which can grow over 70 feet (21 m) tall.

Middle Atlantic coastal forests, typical of the southeastern Atlantic coastal plain, grow around Chesapeake Bay and on the Delmarva Peninsula. Moving west, a mixture of Northeastern coastal forests and Southeastern mixed forests cover the central part of the state. The Appalachian Mountains of western Maryland are home to Appalachian-Blue Ridge forests. These give way to Appalachian mixed mesophytic forests near the West Virginia border.[34]

Many foreign species are cultivated in the state, some as ornamentals, others as novelty species. Included among these are the crape myrtle, Italian cypress, southern magnolia, live oak in the warmer parts of the state,[35] and even hardy palm trees in the warmer central and eastern parts of the state.[36] USDA plant hardiness zones in the state range from Zones 5 and 6 in the extreme western part of the state to Zone 7 in the central part, and Zone 8 around the southern part of the coast, the bay area, and parts of metropolitan Baltimore.[37] Invasive plant species, such as kudzu, tree of heaven, multiflora rose, and Japanese stiltgrass, stifle growth of endemic plant life.[38] Maryland's state flower, the black-eyed susan, grows in abundance in wild flower groups throughout the state.

Fauna

The state harbors a considerable number of white-tailed deer, especially in the woody and mountainous west of the state, and overpopulation can become a problem. Mammals can be found ranging from the mountains in the west to the central areas and include black bears,[39] bobcats,[40] foxes, coyotes,[41] raccoons, and otters.[39]

There is a population of rare wild (feral) horses found on Assateague Island.[42] They are believed to be descended from horses who escaped from Spanish galleon shipwrecks.[42] Every year during the last week of July, they are captured and swim across a shallow bay for sale at Chincoteague, Virginia, a conservation technique which ensures the tiny island is not overrun by the horses.[42] The ponies and their sale were popularized by the children's book, Misty of Chincoteague.

The purebred Chesapeake Bay Retriever dog was bred specifically for water sports, hunting and search and rescue in the Chesapeake area.[43] In 1878, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever was the first individual retriever breed recognized by the American Kennel Club.[43] and was later adopted by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County as their mascot.

Maryland's reptile and amphibian population includes the diamondback terrapin turtle, which was adopted as the mascot of University of Maryland, College Park, as well as the threatened Eastern box turtle.[44] The state is part of the territory of the Baltimore oriole, which is the official state bird and mascot of the MLB team the Baltimore Orioles.[45] Aside from the oriole, 435 other species of birds have been reported from Maryland.[46]

The state insect is the Baltimore checkerspot butterfly, although it is not as common in Maryland as it is in the southern edge of its range.[47]

Environment

Maryland joined with neighboring states during the end of the 20th century to improve the health of the Chesapeake Bay. The bay's aquatic life and seafood industry have been threatened by development and by fertilizer and livestock waste entering the bay.[48][49]

In 2007, Forbes.com rated Maryland as the fifth "Greenest" state in the country behind three of the Pacific States and Vermont. Maryland ranks 40th in total energy consumption nationwide, and it managed less toxic waste per capita than all but six states in 2005.[50] In April 2007 Maryland joined the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI)—a regional initiative formed by all the Northeastern states, Washington, D.C., and three Canadian provinces to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[51] In March 2017, Maryland became the first state with proven gas reserves to ban fracking by passing a law against it. Vermont has such a law, but no shale gas, and New York has such a ban, though it was made by executive order.[32]

Climate

Maryland has a wide array of climates, due to local variances in elevation, proximity to water, and protection from colder weather due to downslope winds.

The eastern half of Maryland—which includes the cities of Ocean City, Salisbury, Annapolis, and the southern and eastern suburbs of Washington, D.C. and Baltimore—lies on the Atlantic Coastal Plain, with flat topography and sandy or muddy soil. This region has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with hot, humid summers and a short, mild to cool winter; it falls under USDA Hardiness zone 8a.[37]

The Piedmont region—which includes northern and western greater Baltimore, Westminster, Gaithersburg, Frederick, and Hagerstown—has average seasonal snowfall totals generally exceeding 20 inches (51 cm) and, as part of USDA Hardiness zones 7b and 7a,[37] temperatures below 10 °F (−12 °C) are less rare. From the Cumberland Valley on westward, the climate begins to transition to a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa).

In western Maryland, the higher elevations of Allegany and Garrett counties—including the cities of Cumberland, Frostburg, and Oakland—display more characteristics of the humid continental zone, due in part to elevation. They fall under USDA Hardiness zones 6b and below.[37]

Precipitation in the state is characteristic of the East Coast. Annual rainfall ranges from 35 to 45 inches (890 to 1,140 mm) with more in higher elevations. Nearly every part of Maryland receives 3.5–4.5 inches (89–114 mm) per month of rain. Average annual snowfall varies from 9 inches (23 cm) in the coastal areas to over 100 inches (250 cm) in the western mountains of the state.[52]

Because of its location near the Atlantic Coast, Maryland is somewhat vulnerable to tropical cyclones, although the Delmarva Peninsula and the outer banks of North Carolina provide a large buffer, such that strikes from major hurricanes (category 3 or above) occur infrequently. More often, Maryland gets the remnants of a tropical system that has already come ashore and released most of its energy. Maryland averages around 30–40 days of thunderstorms a year, and averages around six tornado strikes annually.[53]

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oakland | 34 °F (1 °C) 16 °F (−9 °C) |

38 °F (3 °C) 17 °F (−8 °C) |

48 °F (9 °C) 25 °F (−4 °C) |

59 °F (15 °C) 34 °F (1 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 45 °F (7 °C) |

75 °F (24 °C) 53 °F (12 °C) |

79 °F (26 °C) 58 °F (14 °C) |

78 °F (26 °C) 56 °F (13 °C) |

71 °F (22 °C) 49 °F (9 °C) |

62 °F (17 °C) 37 °F (3 °C) |

50 °F (10 °C) 28 °F (−2 °C) |

39 °F (4 °C) 21 °F (−6 °C) |

| Cumberland | 41 °F (5 °C) 22 °F (−6 °C) |

46 °F (8 °C) 24 °F (−4 °C) |

56 °F (13 °C) 32 °F (0 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 41 °F (5 °C) |

77 °F (25 °C) 51 °F (11 °C) |

85 °F (29 °C) 60 °F (16 °C) |

89 °F (32 °C) 65 °F (18 °C) |

87 °F (31 °C) 63 °F (17 °C) |

80 °F (27 °C) 55 °F (13 °C) |

69 °F (21 °C) 43 °F (6 °C) |

57 °F (14 °C) 34 °F (1 °C) |

45 °F (7 °C) 26 °F (−3 °C) |

| Hagerstown | 39 °F (4 °C) 22 °F (−6 °C) |

42 °F (6 °C) 23 °F (−5 °C) |

52 °F (11 °C) 30 °F (−1 °C) |

63 °F (17 °C) 39 °F (4 °C) |

72 °F (22 °C) 50 °F (10 °C) |

81 °F (27 °C) 59 °F (15 °C) |

85 °F (29 °C) 64 °F (18 °C) |

83 °F (28 °C) 62 °F (17 °C) |

76 °F (24 °C) 54 °F (12 °C) |

65 °F (18 °C) 43 °F (6 °C) |

54 °F (12 °C) 34 °F (1 °C) |

43 °F (6 °C) 26 °F (−3 °C) |

| Frederick | 42 °F (6 °C) 26 °F (−3 °C) |

47 °F (8 °C) 28 °F (−2 °C) |

56 °F (13 °C) 35 °F (2 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 45 °F (7 °C) |

77 °F (25 °C) 54 °F (12 °C) |

85 °F (29 °C) 63 °F (17 °C) |

89 °F (32 °C) 68 °F (20 °C) |

87 °F (31 °C) 66 °F (19 °C) |

80 °F (27 °C) 59 °F (15 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 47 °F (8 °C) |

56 °F (13 °C) 38 °F (3 °C) |

45 °F (7 °C) 30 °F (−1 °C) |

| Baltimore | 42 °F (6 °C) 29 °F (−2 °C) |

46 °F (8 °C) 31 °F (−1 °C) |

54 °F (12 °C) 39 °F (4 °C) |

65 °F (18 °C) 48 °F (9 °C) |

75 °F (24 °C) 57 °F (14 °C) |

85 °F (29 °C) 67 °F (19 °C) |

90 °F (32 °C) 72 °F (22 °C) |

87 °F (31 °C) 71 °F (22 °C) |

80 °F (27 °C) 64 °F (18 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 52 °F (11 °C) |

58 °F (14 °C) 43 °F (6 °C) |

46 °F (8 °C) 33 °F (1 °C) |

| Elkton | 42 °F (6 °C) 24 °F (−4 °C) |

46 °F (8 °C) 26 °F (−3 °C) |

55 °F (13 °C) 32 °F (0 °C) |

67 °F (19 °C) 42 °F (6 °C) |

76 °F (24 °C) 51 °F (11 °C) |

85 °F (29 °C) 61 °F (16 °C) |

88 °F (31 °C) 66 °F (19 °C) |

87 °F (31 °C) 65 °F (18 °C) |

80 °F (27 °C) 57 °F (14 °C) |

69 °F (21 °C) 45 °F (7 °C) |

58 °F (14 °C) 36 °F (2 °C) |

46 °F (8 °C) 28 °F (−2 °C) |

| Ocean City | 45 °F (7 °C) 28 °F (−2 °C) |

46 °F (8 °C) 29 °F (−2 °C) |

53 °F (12 °C) 35 °F (2 °C) |

61 °F (16 °C) 44 °F (7 °C) |

70 °F (21 °C) 53 °F (12 °C) |

79 °F (26 °C) 63 °F (17 °C) |

84 °F (29 °C) 68 °F (20 °C) |

82 °F (28 °C) 67 °F (19 °C) |

77 °F (25 °C) 60 °F (16 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 51 °F (11 °C) |

58 °F (14 °C) 39 °F (4 °C) |

49 °F (9 °C) 32 °F (0 °C) |

| Waldorf | 44 °F (7 °C) 26 °F (−3 °C) |

49 °F (9 °C) 28 °F (−2 °C) |

58 °F (14 °C) 35 °F (2 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 43 °F (6 °C) |

75 °F (24 °C) 53 °F (12 °C) |

81 °F (27 °C) 62 °F (17 °C) |

85 °F (29 °C) 67 °F (19 °C) |

83 °F (28 °C) 65 °F (18 °C) |

78 °F (26 °C) 59 °F (15 °C) |

68 °F (20 °C) 47 °F (8 °C) |

59 °F (15 °C) 38 °F (3 °C) |

48 °F (9 °C) 30 °F (−1 °C) |

| Point Lookout State Park | 47 °F (8 °C) 29 °F (−2 °C) |

51 °F (11 °C) 31 °F (−1 °C) |

60 °F (16 °C) 38 °F (3 °C) |

70 °F (21 °C) 46 °F (8 °C) |

78 °F (26 °C) 55 °F (13 °C) |

86 °F (30 °C) 64 °F (18 °C) |

89 °F (32 °C) 69 °F (21 °C) |

87 °F (31 °C) 67 °F (19 °C) |

81 °F (27 °C) 60 °F (16 °C) |

71 °F (22 °C) 49 °F (9 °C) |

61 °F (16 °C) 41 °F (5 °C) |

50 °F (10 °C) 32 °F (0 °C) |

| [54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63] | ||||||||||||

History

17th century

Maryland's first colonial settlement

George Calvert, 1st Lord Baltimore (1579–1632), sought a charter from King Charles I for the territory between Massachusetts to the north and Virginia to the immediate south.[64] After the first Lord Baltimore died in April 1632, the charter was granted to his son, Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore (1605–1675), on June 20, 1632. Officially, the new "Maryland Colony" was named in honor of Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I of England.[65] The 1st Lord Baltimore initially proposed the name "Crescentia", the land of growth or increase, but "the King proposed Terra Mariae [Mary Land], which was concluded on and Inserted in the bill."[19]

The original capital of Maryland was St. Mary's City, on the north shore of the Potomac River, and the county surrounding it, the first erected/created in the province,[66] was first called Augusta Carolina, after the King, and later named St. Mary's County.[67]

Lord Baltimore's first settlers arrived in the new colony in March 1634, with his younger brother the Honorable Leonard Calvert (1606–1647), as first provincial Governor of Maryland. They made their first permanent settlement at St. Mary's City in what is now St. Mary's County. They purchased the site from the paramount chief of the region, who was eager to establish trade. St. Mary's became the first capital of Maryland, and remained so for 60 years until 1695. More settlers soon followed. Their tobacco crops were successful and quickly made the new colony profitable. However, given the incidence of malaria, yellow fever and typhoid, life expectancy in Maryland was about 10 years less than in New England.[68]

Persecution of Catholics

Maryland was founded to provide a haven for England's Roman Catholic minority.[69] Although Maryland was the most heavily Catholic of the English mainland colonies, the religion was still in the minority, consisting of less than 10% of the total population.[70]

In 1642, a number of Puritans left Virginia for Maryland and founded Providence (now called Annapolis) on the western shore of the upper Chesapeake Bay.[71] A dispute with traders from Virginia over Kent Island in the Chesapeake led to armed conflict. In 1644, William Claiborne, a Puritan, seized Kent Island while his associate, the pro-Parliament Puritan Richard Ingle, took over St. Mary's.[72] Both used religion as a tool to gain popular support. The two years from 1644 to 1646 when Claiborne and his Puritan associates held sway were known as "The Plundering Time". They captured Jesuit priests, imprisoned them, then sent them back to England.

In 1646 Leonard Calvert returned with troops, recaptured St. Mary's City, and restored order. The House of Delegates passed the "Act concerning Religion" in 1649 granting religious liberty to all Trinitarian Christians.[68]

In 1650, the Puritans revolted against the proprietary government. "Protestants swept the Catholics out of the legislature ... and religious strife returned."[68] The Puritans set up a new government prohibiting both Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism. The Puritan revolutionary government persecuted Maryland Catholics during its reign, known as the "plundering time". Mobs burned down all the original Catholic churches of southern Maryland. The Puritan rule lasted until 1658 when the Calvert family and Lord Baltimore regained proprietary control and re-enacted the Toleration Act.

After England's "Glorious Revolution" of 1688, Maryland outlawed Catholicism. In 1704, the Maryland General Assembly prohibited Catholics from operating schools, limited the corporate ownership of property to hamper religious orders from expanding or supporting themselves, and encouraged the conversion of Catholic children.[70] The celebration of the Catholic sacraments was also officially restricted. This state of affairs lasted until after the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783). Wealthy Catholic planters built chapels on their land to practice their religion in relative secrecy.

Into the 18th century, individual priests and lay leaders claimed Maryland farms belonging to the Jesuits as personal property and bequeathed them in order to evade the legal restrictions on religious organizations' owning property.[70]

Border disputes (1681–1760)

The royal charter granted Maryland the land north of the Potomac River up to the 40th parallel. A problem arose when Charles II granted a charter for Pennsylvania. The grant defined Pennsylvania's southern border as identical to Maryland's northern border, the 40th parallel. But the grant indicated that Charles II and William Penn assumed the 40th parallel would pass close to New Castle, Delaware when it falls north of Philadelphia, the site of which Penn had already selected for his colony's capital city. Negotiations ensued after the problem was discovered in 1681.

A compromise proposed by Charles II in 1682 was undermined by Penn's receiving the additional grant of what is now Delaware.[73] Penn successfully argued that the Maryland charter entitled Lord Baltimore only to unsettled lands, and Dutch settlement in Delaware predated his charter. The dispute remained unresolved for nearly a century, carried on by the descendants of William Penn and Lord Baltimore—the Calvert family, which controlled Maryland, and the Penn family, which controlled Pennsylvania.[73]

The border dispute with Pennsylvania led to Cresap's War in the 1730s. Hostilities erupted in 1730 and escalated through the first half of the decade, culminating in the deployment of military forces by Maryland in 1736 and by Pennsylvania in 1737. The armed phase of the conflict ended in May 1738 with the intervention of King George II, who compelled the negotiation of a cease-fire. A provisional agreement had been established in 1732.[73]

Negotiations continued until a final agreement was signed in 1760. The agreement defined the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania as the line of latitude now known as the Mason–Dixon line. Maryland's border with Delaware was based on a Transpeninsular Line and the Twelve-Mile Circle around New Castle.[73]

18th century

Most of the English colonists arrived in Maryland as indentured servants, and had to serve a several years' term as laborers to pay for their passage.[75] In the early years, the line between indentured servants and African slaves or laborers was fluid, and white and black laborers commonly lived and worked together, and formed unions. Mixed-race children born to white mothers were considered free by the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, by which children took the social status of their mothers, a principle of slave law that was adopted throughout the colonies, following Virginia in 1662. During the colonial era, families of free people of color were formed most often by unions of white women and African men.[76]

Many of the free black families migrated to Delaware, where land was cheaper.[76] As the flow of indentured laborers to the colony decreased with improving economic conditions in England, planters in Maryland imported thousands more slaves and racial caste lines hardened. The economy's growth and prosperity were based on slave labor, devoted first to the production of tobacco as the commodity crop.

Maryland was one of the thirteen colonies that revolted against British rule in the American Revolution. Near the end of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), on February 2, 1781, Maryland became the last and 13th state to approve the ratification of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, first proposed in 1776 and adopted by the Second Continental Congress in 1778, which brought into being the United States as a united, sovereign and national state. It also became the seventh state admitted to the Union after ratifying the new federal Constitution in 1788. In December 1790, Maryland donated land selected by first President George Washington to the federal government for the creation of the new national capital of Washington, D.C. The land was provided along the north shore of the Potomac River from Montgomery and Prince George's counties, as well as from Fairfax County and Alexandria on the south shore of the Potomac in Virginia; however, the land donated by the Commonwealth of Virginia was later returned to that state by the District of Columbia retrocession in 1846.

19th century

This section possibly contains original research. (May 2014) |

Influenced by a changing economy, revolutionary ideals, and preaching by ministers, numerous planters in Maryland freed their slaves in the 20 years after the Revolutionary War. Across the Upper South the free black population increased from less than 1% before the war to 14% by 1810.[77] Abolitionist Harriet Tubman was born a slave during this time in Dorchester County, Maryland.[78]

During the War of 1812, the British military attempted to capture Baltimore, which was protected by Fort McHenry. During this bombardment the song "Star Spangled Banner" was written by Francis Scott Key; it was later adopted as the national anthem.

The National Road (U.S. Hwy 40 today) was authorized in 1817 and ran from Baltimore to St. Louis—the first federal highway. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) was the first chartered railroad in the United States. It opened its first section of track for regular operation in 1830 between Baltimore and Ellicott City,[79] and in 1852 it became the first rail line to reach the Ohio River from the eastern seaboard.[80]

Civil War

The state remained with the Union during the Civil War,[81] due in significant part to demographics and Federal intervention. The 1860 census, held shortly before the outbreak of the civil war, showed that 49% of Maryland's African Americans were free blacks.[77]

Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks suspended the state legislature, and to help ensure the election of a new pro-union governor and legislature, President Abraham Lincoln had a number of its pro-slavery politicians arrested, including the Mayor of Baltimore, George William Brown; suspended several civil liberties, including habeas corpus; and ordered artillery placed on Federal Hill overlooking Baltimore. Historians debate the constitutionality of these wartime actions, and the suspension of civil liberties was later deemed illegal by the U.S. Supreme Court.[citation needed]

In April 1861 Federal units and state regiments were attacked as they marched through Baltimore, sparking the Baltimore riot of 1861, the first bloodshed in the Civil War.[82] Of the 115,000 men from Maryland who joined the military during the Civil War, 85,000, or 77%, joined the Union army, while the remainder joined the Confederate Army.[citation needed] The largest and most significant battle in the state was the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg. Although a tactical draw, the battle was considered a strategic Union victory and a turning point of the war.

After the war

A new state constitution in 1864 abolished slavery and Maryland was first recognized as a "Free State" in that context.[83] Following passage of constitutional amendments that granted voting rights to freedmen, in 1867 the state extended suffrage to non-white males.

The Democratic Party rapidly regained power in the state from Republicans. Democrats replaced the Constitution of 1864 with the Constitution of 1867. Following the end of Reconstruction in 1877, Democrats devised means of disenfranchising blacks, initially by physical intimidation and voter fraud, later by constitutional amendments and laws. Blacks and immigrants, however, resisted Democratic Party disfranchisement efforts in the state. Maryland blacks were part of a biracial Republican coalition elected to state government in 1896–1904 and comprised 20% of the electorate.[84]

Compared to some other states, blacks were better established both before and after the civil war. Nearly half the black population was free before the war, and some had accumulated property. Half the population lived in cities. Literacy was high among blacks and, as Democrats crafted means to exclude them, suffrage campaigns helped reach blacks and teach them how to resist.[84] Whites did impose racial segregation in public facilities and Jim Crow laws, which effectively lasted until the passage of federal civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s.

Baltimore grew significantly during the Industrial Revolution, due in large part to its seaport and good railroad connections, attracting European immigrant labor. Many manufacturing businesses were established in the Baltimore area after the Civil War. Baltimore businessmen, including Johns Hopkins, Enoch Pratt, George Peabody, and Henry Walters, founded notable city institutions that bear their names, including a university, library, music school and art museum.

Cumberland was Maryland's second-largest city in the 19th century. Nearby supplies of natural resources along with railroads fostered its growth into a major manufacturing center.[85]

20th and 21st centuries

This section possibly contains original research. (May 2014) |

Early 20th century

The Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought political reforms. In a series of laws passed between 1892 and 1908, reformers worked for standard state-issued ballots (rather than those distributed and marked by the parties); obtained closed voting booths to prevent party workers from "assisting" voters; initiated primary elections to keep party bosses from selecting candidates; and had candidates listed without party symbols, which discouraged the illiterate from participating. These measures worked against ill-educated whites and blacks. Blacks resisted such efforts, with suffrage groups conducting voter education. Blacks defeated three efforts to disenfranchise them, making alliances with immigrants to resist various Democratic campaigns.[84] Disenfranchisement bills in 1905, 1907, and 1911 were rebuffed, in large part because of black opposition. Blacks comprised 20% of the electorate and immigrants comprised 15%, and the legislature had difficulty devising requirements against blacks that did not also disadvantage immigrants.[84]

The Progressive Era also brought reforms in working conditions for Maryland's labor force. In 1902, the state regulated conditions in mines; outlawed child laborers under the age of 12; mandated compulsory school attendance; and enacted the nation's first workers' compensation law. The workers' compensation law was overturned in the courts, but was redrafted and finally enacted in 1910.

The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 burned for more than 30 hours, destroying 1,526 buildings and spanning 70 city blocks. More than 1,231 firefighters worked to bring the blaze under control.

With the nation's entry into World War I in 1917, new military bases such as Camp Meade, the Aberdeen Proving Ground, and the Edgewood Arsenal were established. Existing facilities, including Fort McHenry, were greatly expanded.

After Georgia congressman William D. Upshaw criticized Maryland openly in 1923 for not passing Prohibition laws, Baltimore Sun editor Hamilton Owens coined the "Free State" nickname for Maryland in that context, which was popularized by H. L. Mencken in a series of newspaper editorials.[83][86]

Maryland's urban and rural communities had different experiences during the Great Depression. The "Bonus Army" marched through the state in 1932 on its way to Washington, D.C. Maryland instituted its first income tax in 1937 to generate revenue for schools and welfare.[87]

Passenger and freight steamboat service, once important throughout Chesapeake Bay and its many tributary rivers, ended in 1962.[88]

Baltimore was a major war production center during World War II. The biggest operations were Bethlehem Steel's Fairfield Yard, which built Liberty ships; and Glenn Martin, an aircraft manufacturer.

1950–present

Maryland experienced population growth following World War II. Beginning in the 1960s, as suburban growth took hold around Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, the state began to take on a more mid-Atlantic culture as opposed to the traditionally Southern and Tidewater culture that previously dominated most of the state. Agricultural tracts gave way to residential communities, some of them carefully planned such as Columbia, St. Charles, and Montgomery Village. Concurrently the Interstate Highway System was built throughout the state, most notably I-95, I-695, and the Capital Beltway, altering travel patterns. In 1952, the eastern and western halves of Maryland were linked for the first time by the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, which replaced a nearby ferry service.[89]

Maryland's regions experienced economic changes following WWII. Heavy manufacturing declined in Baltimore. In Maryland's four westernmost counties, industrial, railroad, and coal mining jobs declined. On the lower Eastern Shore, family farms were bought up by major concerns and large-scale poultry farms and vegetable farming became prevalent. In Southern Maryland, tobacco farming nearly vanished due to suburban development and a state tobacco buy-out program in the 1990s.

In an effort to reverse depopulation due to the loss of working-class industries, Baltimore initiated urban renewal projects in the 1960s with Charles Center and the Baltimore World Trade Center. Some resulted in the break-up of intact residential neighborhoods, producing social volatility, and some older residential areas around the harbor have had units renovated and have become popular with new populations.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 319,728 | — | |

| 1800 | 341,548 | 6.8% | |

| 1810 | 380,546 | 11.4% | |

| 1820 | 407,350 | 7.0% | |

| 1830 | 447,040 | 9.7% | |

| 1840 | 470,019 | 5.1% | |

| 1850 | 583,034 | 24.0% | |

| 1860 | 687,049 | 17.8% | |

| 1870 | 780,894 | 13.7% | |

| 1880 | 934,943 | 19.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,042,390 | 11.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,188,044 | 14.0% | |

| 1910 | 1,295,346 | 9.0% | |

| 1920 | 1,449,661 | 11.9% | |

| 1930 | 1,631,526 | 12.5% | |

| 1940 | 1,821,244 | 11.6% | |

| 1950 | 2,343,001 | 28.6% | |

| 1960 | 3,100,689 | 32.3% | |

| 1970 | 3,922,399 | 26.5% | |

| 1980 | 4,216,975 | 7.5% | |

| 1990 | 4,781,468 | 13.4% | |

| 2000 | 5,296,486 | 10.8% | |

| 2010 | 5,773,552 | 9.0% | |

| 2020 | 6,177,224 | 7.0% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[90] | |||

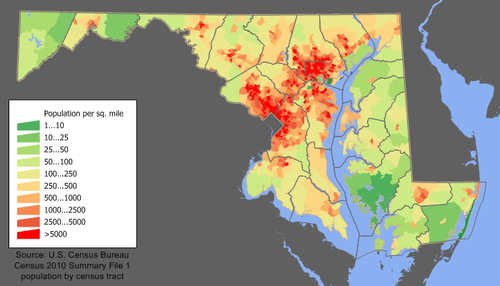

In the 2020 United States Census, the United States Census Bureau found that population of Maryland was 6,185,278 people, a 7.1% increase from the 2010 United States Census.[8] The United States Census Bureau estimated that the population of Maryland was 6,045,680 on July 1, 2019, a 4.71% increase from the 2010 United States Census and an increase of 2,962, from the prior year. This includes a natural increase since the last census of 269,166 (464,251 births minus 275,093 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 116,713 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 129,730 people, and migration within the country produced a net loss of 13,017 people.[91] The center of population of Maryland is located on the county line between Anne Arundel County and Howard County, in the unincorporated community of Jessup.[92]

Maryland's history as a border state has led it to exhibit characteristics of both the Northern and the Southern regions of the United States. Generally, rural Western Maryland between the West Virginian Panhandle and Pennsylvania has an Appalachian culture; the Southern and Eastern Shore regions of Maryland embody a Southern culture,[93] while densely populated Central Maryland—radiating outward from Baltimore and Washington, D.C.—has more in common with that of the Northeast.[94] The U.S. Census Bureau designates Maryland as one of the South Atlantic States, but it is commonly associated with the Mid-Atlantic States and Northeastern United States by other federal agencies, the media, and some residents.[95][96][97][98][99]

Birth data

As of 2011, 58.0 percent of Maryland's population younger than age 1 were minority background.[100]

Note: Births in table don't add up because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[101] | 2014[102] | 2015[103] | 2016[104] | 2017[105] | 2018[106] | 2019[107] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 41,474 (57.6%) | 42,525 (57.5%) | 42,471 (57.7%) | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 32,568 (45.2%) | 33,178 (44.9%) | 32,412 (44.0%) | 31,278 (42.8%) | 29,809 (41.6%) | 29,585 (41.6%) | 28,846 (41.1%) |

| Black | 24,764 (34.4%) | 25,339 (34.3%) | 25,017 (34.0%) | 22,829 (31.2%) | 22,327 (31.1%) | 21,893 (30.8%) | 21,494 (30.6%) |

| Asian | 5,415 (7.5%) | 5,797 (7.8%) | 5,849 (7.9%) | 5,282 (7.2%) | 5,276 (7.3%) | 4,928 (6.9%) | 4,928 (7.0%) |

| American Indian | 300 (0.4%) | 260 (0.3%) | 279 (0.4%) | 104 (0.1%) | 127 (0.2%) | 114 (0.2%) | 113 (0.2%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 10,515 (14.6%) | 10,974 (14.8%) | 11,750 (16.0%) | 11,872 (16.2%) | 12,223 (17.1%) | 12,470 (17.5%) | 12,872 (18.3%) |

| Total Maryland | 71,953 (100%) | 73,921 (100%) | 73,616 (100%) | 73,136 (100%) | 71,641 (100%) | 71,080 (100%) | 70,178 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Language

Spanish (including Spanish Creole) is the second most spoken language in Maryland, after English. The third and fourth most spoken languages are French (including Patois and Cajun) and Chinese. Other commonly spoken languages include various African languages, Korean, German, Tagalog, Russian, Vietnamese, Italian, various Asian languages, Persian, Hindi and other Indic languages, Greek and Arabic.[108]

Cities and metro areas

Most of the population of Maryland lives in the central region of the state, in the Baltimore metropolitan area and Washington metropolitan area, both of which are part of the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area. The majority of Maryland's population is concentrated in the cities and suburbs surrounding Washington, D.C., as well as in and around Maryland's most populous city, Baltimore. Historically, these and many other Maryland cities developed along the Fall Line, the line along which rivers, brooks, and streams are interrupted by rapids and waterfalls. Maryland's capital city, Annapolis, is one exception to this pattern since it lies along the banks of the Severn River, close to where it empties into the Chesapeake Bay.

The Eastern Shore is less populous and more rural, as are the counties of western Maryland. The two westernmost counties of Maryland, Allegany and Garrett, are mountainous and sparsely populated, resembling West Virginia and Appalachia more than they do the rest of the state. Both eastern and western Maryland are, however, dotted with cities of regional importance, such as Ocean City, Princess Anne, and Salisbury on the Eastern Shore and Cumberland, Frostburg, and Hancock in Western Maryland. Southern Maryland is still somewhat rural, but suburbanization from Washington, D.C. has encroached significantly since the 1960s; important local population centers include Lexington Park, Prince Frederick, California, and Waldorf.[109][110]

| Rank | County | Pop. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baltimore  Columbia |

1 | Baltimore | Independent city | 620,961 |  Germantown  Silver Spring | ||||

| 2 | Columbia | Howard | 99,615 | ||||||

| 3 | Germantown | Montgomery | 86,395 | ||||||

| 4 | Silver Spring | Montgomery | 71,452 | ||||||

| 5 | Waldorf | Charles | 67,752 | ||||||

| 6 | Glen Burnie | Anne Arundel | 67,639 | ||||||

| 7 | Ellicott City | Howard | 65,834 | ||||||

| 8 | Frederick | Frederick | 65,239 | ||||||

| 9 | Dundalk | Baltimore | 63,597 | ||||||

| 10 | Rockville | Montgomery | 61,209 | ||||||

Ancestry

Racial Makeup of Maryland excluding Hispanics from racial categories (2019)[111]

NH = Non-Hispanic

| Racial composition | 1970[112] | 1990[112] | 2000[113] | 2010[114] | 2019[115] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 81.5% | 71.0% | 64.0% | 60.8% | |

| Black | 17.8% | 24.9% | 27.9% | 29.8% | 29.75% |

| Asian | 0.5% | 2.9% | 4.0% | 5.5% | 6.35% |

| Native | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.25% |

| Other race | 0.1% | 0.9% | 1.8% | 3.6% | |

| Two or more races | – | – | 2.0% | 2.9% | 2.85% |

| Non-Hispanic whites | 80.4% | 69.6% | 62.1% | 54.7% | 49.82% |

In 1970 the Census Bureau reported Maryland's population as 17.8 percent African-American and 80.4 percent non-Hispanic White.[116]

African Americans form a sizable portion of the state's population, nearly 30 percent in 2010.[117] Most are descendants of people transported to the area as slaves from West Africa, and many are of mixed race, including European and Native American ancestry. Concentrations of African Americans live in Baltimore City, Prince George's County, a suburb of Washington, D.C., where many work; Charles County, western parts of Baltimore County, and the southern Eastern Shore. New residents of African descent include 20th-century and later immigrants from Nigeria, particularly of the Igbo and Yoruba tribes.[118] Maryland also hosts populations from other African and Caribbean nations. Many immigrants from the Horn of Africa have settled in Maryland, with large communities existing in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. (particularly Montgomery County and Prince George's County) and the city of Baltimore. The Greater Washington area has the largest population of Ethiopians outside of Africa.[119] The Ethiopian community of Greater D.C. was historically based in Washington, D.C.'s Adams Morgan and Shaw neighborhoods, but as the community has grown, many Ethiopians have settled in Silver Spring.[120] The Washington, D.C. metropolitan area is also home to large Eritrean and Somali communities.

The top reported ancestries by Maryland residents are: German (15%), Irish (11%), English (8%), American (7%), Italian (6%), and Polish (3%).[121]

Irish American populations can be found throughout the Baltimore area,[122] and the Northern and Eastern suburbs of Washington, D.C. in Maryland (descendants of those who moved out to the suburbs[123] of Washington's once predominantly Irish neighborhoods[123][115]), as well as Western Maryland, where Irish immigrant laborers helped to build the B & O Railroad.[122] Smaller but much older Irish populations can be found in Southern Maryland, with some roots dating as far back as the early Maryland colony.[124] This population, however, still remains culturally very active and yearly festivals are held.[125]

A large percentage of the population of the Eastern Shore and Southern Maryland are descendants of British American ancestry. The Eastern Shore was settled by Protestants, chiefly Methodist and the southern counties were initially settled by English Catholics. Western and northern Maryland have large German-American populations. More recent European immigrants of the late 19th and early 20th century settled first in Baltimore, attracted to its industrial jobs. Many of their ethnic Italian, Polish, Czech, Lithuanian, and Greek descendants still live in the area.

Large ethnic minorities include Eastern Europeans such as Croatians, Belarusians, Russians and Ukrainians. The shares of European immigrants born in Eastern Europe increased significantly between 1990 and 2010. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, many immigrants from Eastern Europe came to the United States—12 percent of whom currently reside in Maryland.[126][127]

Hispanic immigrants of the later 20th century have settled in Aspen Hill, Hyattsville/Langley Park, Glenmont/Wheaton, Bladensburg, Riverdale Park, Gaithersburg, as well as Highlandtown and Greektown in East Baltimore. Salvadorans are the largest Hispanic group in Maryland. Other Hispanic groups with significant populations in the state include Mexicans and Puerto Ricans and Hondurans. Though the Salvadoran population is more concentrated in the area around Washington, D.C., and the Puerto Rican population is more concentrated in the Baltimore area, all other major Hispanic groups in the state are evenly dispersed between these two areas. Maryland has one of the most diverse Hispanic populations in the country, with significant populations from various Caribbean and Central American nations.[128]

Asian Americans are concentrated in the suburban counties surrounding Washington, D.C. and in Howard County, with Korean American and Taiwanese American communities in Rockville, Gaithersburg, and Germantown and a Filipino American community in Fort Washington. Numerous Indian Americans live across the state, especially in central Maryland.

Attracting educated Asians and Africans to the professional jobs in the region, Maryland has the fifth-largest proportions of racial minorities in the country.[129]

In 2006 645,744 were counted as foreign born, which represents mainly people from Latin America and Asia. About four percent are undocumented immigrants.[130] Maryland also has a large Korean American population.[131] In fact, 1.7 percent are Korean, while as a whole, almost 6.0 percent are Asian.[132]

According to The Williams Institute's analysis of the 2010 U.S. Census, 12,538 same-sex couples are living in Maryland, representing 5.8 same-sex couples per 1,000 households.[133]

As of 2019, non-Hispanic white Americans were 49.8% of Maryland's population (White Americans, including White Hispanics, were 57.3%), making Maryland a majority minority state.[134] 50.2% of Maryland's population is non-white or is Hispanic or Latino, the highest percentage of any state on the East Coast and the highest percentage after the majority minority states of Hawaii, New Mexico, Texas, California and Nevada.[135] By 2031, minorities are projected to become the majority of voting eligible residents of Maryland.[136]

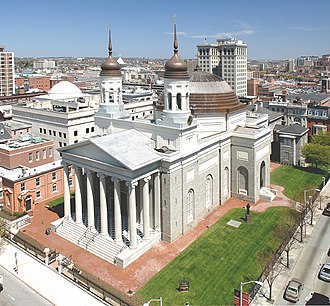

Religion

Maryland has been historically prominent to American Catholic tradition because the English colony of Maryland was intended by George Calvert as a haven for English Catholics. Baltimore was the seat of the first Catholic bishop in the U.S. (1789), and Emmitsburg was the home and burial place of the first American-born citizen to be canonized, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton. Georgetown University, the first Catholic University, was founded in 1789 in what was then part of Maryland.[138] The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Baltimore was the first Roman Catholic cathedral built in the United States, and the Archbishop of Baltimore is, albeit without formal primacy, the United States' quasi-primate,[citation needed] and often a cardinal. Among the immigrants of the 19th and 20th centuries from eastern and southern Europe were many Catholics.

Despite its historic relevance to the Catholic Church in the United States, the percentage of Catholics in the state of Maryland is below the national average of 20%. Demographically, both Protestants and those identifying no religion are more numerous than Catholics.

According to Pew Research Center, 69 percent of Maryland's population identifies themselves as Christian. Nearly 52% of the adult population are Protestants.[lower-alpha 2] Following Protestantism, Catholicism is the second largest religious affiliation, comprising 15% percent of the population.[137][139] Amish/Mennonite communities are found in St. Mary's, Garrett, and Cecil counties.[140] Judaism is the largest non-Christian religion in Maryland with 241,000 adherents, or four percent of the total population.[141] Jews are numerous throughout Montgomery County and in Pikesville and Owings Mills northwest of Baltimore. An estimated 81,500 Jewish Americans live in Montgomery County, constituting approximately 10% of the total population.[142] The Seventh-day Adventist Church's world headquarters and Ahmadiyya Muslims' national headquarters are located in Silver Spring, just outside the District of Columbia.

Economy

The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that Maryland's gross state product in 2016 was $382.4 billion.[143] However, Maryland has been using Genuine Progress Indicator, an indicator of well-being, to guide the state's development, rather than relying only on growth indicators like GDP.[144][145] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Maryland households are currently the wealthiest in the country, with a 2013 median household income of $72,483[146] which puts it ahead of New Jersey and Connecticut, which are second and third respectively. Two of Maryland's counties, Howard and Montgomery, are the second and eleventh wealthiest counties in the nation respectively. Maryland has the most millionaires per capita in 2013, with a ratio of 7.7 percent.[147] Also, the state's poverty rate of 7.8 percent is the lowest in the country.[148][149][150] per capita personal income in 2006 was $43,500, fifth in the nation. As of February 2018, the state's unemployment rate was 4.2 percent.[151]

Maryland's economy benefits from the state's proximity to the federal government in Washington, D.C. with an emphasis on technical and administrative tasks for the defense/aerospace industry and bio-research laboratories, as well as staffing of satellite government headquarters in the suburban or exurban Baltimore/Washington area. Ft. Meade serves as the headquarters of the Defense Information Systems Agency, United States Cyber Command, and the National Security Agency/Central Security Service. In addition, a number of educational and medical research institutions are located in the state. In fact, the various components of The Johns Hopkins University and its medical research facilities are now the largest single employer in the Baltimore area. Altogether, white collar technical and administrative workers comprise 25 percent of Maryland's labor force,[citation needed] attributable in part to nearby Maryland being a part of the Washington Metro Area where the federal government office employment is relatively high.

Manufacturing, while large in dollar value, is highly diversified with no sub-sector contributing over 20 percent of the total. Typical forms of manufacturing include electronics, computer equipment, and chemicals. The once-mighty primary metals sub-sector, which once included what was then the largest steel factory in the world at Sparrows Point, still exists, but is pressed with foreign competition, bankruptcies, and mergers. During World War II the Glenn Martin Company (now part of Lockheed Martin) airplane factory employed some 40,000 people.

Mining other than construction materials is virtually limited to coal, which is located in the mountainous western part of the state. The brownstone quarries in the east, which gave Baltimore and Washington much of their characteristic architecture in the mid-19th century, were once a predominant natural resource. Historically, there used to be small gold-mining operations in Maryland, some near Washington, but these no longer exist.

Baltimore port

One major service activity is transportation, centered on the Port of Baltimore and its related rail and trucking access. The port ranked 17th in the U.S. by tonnage in 2008.[152] Although the port handles a wide variety of products, the most typical imports are raw materials and bulk commodities, such as iron ore, petroleum, sugar, and fertilizers, often distributed to the relatively close manufacturing centers of the inland Midwest via good overland transportation. The port also receives several brands of imported motor vehicles and is the number one auto port in the U.S.[153]

Baltimore City is among the top 15 largest ports in the nation,[154] and was one of six major U.S. ports that were part of the February 2006 controversy over the Dubai Ports World deal.[155] The state as a whole is heavily industrialized, with a booming economy and influential technology centers. Its computer industries are some of the most sophisticated in the United States, and the federal government has invested heavily in the area. Maryland is home to several large military bases and scores of high-level government jobs.

The Chesapeake and Delaware Canal is a 14 miles (23 km) canal on the Eastern Shore that connects the waters of the Delaware River with those of the Chesapeake Bay, and in particular with the Port of Baltimore, carrying 40 percent of the port's ship traffic.[156]

Agriculture and fishing

Maryland has a large food-production sector. A large component of this is commercial fishing, centered in the Chesapeake Bay, but also including activity off the short Atlantic seacoast. The largest catches by species are the blue crab, oysters, striped bass, and menhaden. The Bay also has overwintering waterfowl in its wildlife refuges. The waterfowl support a tourism sector of sportsmen.

Maryland has large areas of fertile agricultural land in its coastal and Piedmont zones, though this land use is being encroached upon by urbanization. Agriculture is oriented to dairy farming (especially in foothill and piedmont areas) for nearby large city milksheads plus specialty perishable horticulture crops, such as cucumbers, watermelons, sweet corn, tomatoes, muskmelons, squash, and peas (Source:USDA Crop Profiles). The southern counties of the western shoreline of Chesapeake Bay are warm enough to support a tobacco cash crop zone, which has existed since early Colonial times but declined greatly after a state government buyout in the 1990s. There is also a large automated chicken-farming sector in the state's southeastern part; Salisbury is home to Perdue Farms. Maryland's food-processing plants are the most significant type of manufacturing by value in the state.

Biotechnology

Maryland is a major center for life sciences research and development. With more than 400 biotechnology companies located there, Maryland is the fourth-largest nexus in this field in the United States.[157]

Institutions and government agencies with an interest in research and development located in Maryland include the Johns Hopkins University, the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, more than one campus of the University System of Maryland, Goddard Space Flight Center, the United States Census Bureau, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Celera Genomics company, the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), and AstraZeneca (formerly MedImmune).

Maryland is home to defense contractor Emergent BioSolutions, which manufactures and provides an anthrax vaccine to U.S. government military personnel.[158]

Tourism

Tourism is popular in Maryland. Many tourists visit Baltimore, the beaches of the Eastern Shore, and the nature of western Maryland. Attractions in Baltimore include the Harborplace, the Baltimore Aquarium, Fort McHenry, as well as the Camden Yards baseball stadium. Ocean City on the Atlantic Coast has been a popular beach destination in summer, particularly since the Chesapeake Bay Bridge was built in 1952 connecting the Eastern Shore to the more populated Maryland cities.[89] The state capital of Annapolis offers sites such as the state capitol building, the historic district, and the waterfront. Maryland also has several sites of interest to military history, given Maryland's role in the American Civil War and in the War of 1812. Other attractions include the historic and picturesque towns along the Chesapeake Bay, such as Saint Mary's, Maryland's first colonial settlement and original capital.[159]

Healthcare

As of 2017, the top two health insurers including all types of insurance were CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield with 47% market share followed by UnitedHealth Group at 15%.[160]

Maryland has experimented with healthcare payment reforms, notably beginning in the 1970s with an all-payer rate setting program regulated by the Health Services Cost Review Commission.[161] In 2014, it switched to a global budget revenue system, whereby hospitals receive a capitated payment to care for their population.[161]

Transportation

The Maryland Department of Transportation oversees most transportation in the state through its various administration-level agencies.[162] The independent Maryland Transportation Authority maintains and operates the state's eight toll facilities.

Roads

Maryland's Interstate highways include 110 miles (180 km) of Interstate 95 (I-95), which enters the northeast portion of the state, travels through Baltimore, and becomes part of the eastern section of the Capital Beltway to the Woodrow Wilson Bridge. I-68 travels 81 miles (130 km), connecting the western portions of the state to I-70 at the small town of Hancock. I-70 enters from Pennsylvania north of Hancock and continues east for 93 miles (150 km) to Baltimore, connecting Hagerstown and Frederick along the way.

I-83 has 34 miles (55 km) in Maryland and connects Baltimore to southern central Pennsylvania (Harrisburg and York, Pennsylvania). Maryland also has an 11-mile (18 km) portion of I-81 that travels through the state near Hagerstown. I-97, fully contained within Anne Arundel County and the shortest (17.6 miles (28.3 km)) one- or two-digit interstate highway in the contiguous US, connects the Baltimore area to the Annapolis area.

There are also several auxiliary Interstate highways in Maryland. Among them are two beltways encircling the major cities of the region: I-695, the McKeldin (Baltimore) Beltway, which encircles Baltimore; and a portion of I-495, the Capital Beltway, which encircles Washington, D.C. I-270, which connects the Frederick area with Northern Virginia and the District of Columbia through major suburbs to the northwest of Washington, is a major commuter route and is as wide as fourteen lanes at points. I-895, also known as the Harbor Tunnel Thruway, provides an alternate route to I-95 across the Baltimore Harbor.

Both I-270 and the Capital Beltway were extremely congested; however, the Intercounty Connector (ICC; MD 200) has alleviated some congestion over time. Construction of the ICC was a major part of the campaign platform of former Governor Robert Ehrlich, who was in office from 2003 until 2007, and of Governor Martin O'Malley, who succeeded him. I-595, which is an unsigned highway concurrent with US 50/US 301, is the longest unsigned interstate in the country and connects Prince George's County and Washington, D.C. with Annapolis and the Eastern Shore via the Chesapeake Bay Bridge.

Maryland also has a state highway system that contains routes numbered from 2 through 999, however most of the higher-numbered routes are either unsigned or are relatively short. Major state highways include Routes 2 (Governor Ritchie Highway/Solomons Island Road/Southern Maryland Blvd.), 4 (Pennsylvania Avenue/Southern Maryland Blvd./Patuxent Beach Road/St. Andrew's Church Road), 5 (Branch Avenue/Leonardtown Road/Point Lookout Road), 32, 45 (York Road), 97 (Georgia Avenue), 100 (Paul T. Pitcher Memorial Highway), 210 (Indian Head Highway), 235 (Three Notch Road), 295 (Baltimore-Washington Parkway), 355 (Wisconsin Avenue/Rockville Pike/Frederick Road), 404 (Queen Anne Highway/ Shore Highway), and 650 (New Hampshire Avenue).

Airports

Maryland's largest airport is Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, more commonly referred to as BWI. The airport is named for the Baltimore-born Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American Supreme Court justice. The only other airports with commercial service are at Hagerstown and Salisbury.

The Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C. are also served by the other two airports in the region, Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and Dulles International Airport, both in Northern Virginia. The College Park Airport is the nation's oldest, founded in 1909, and is still used. Wilbur Wright trained military aviators at this location.[163][164]

Rail

Amtrak trains, including the high-speed Acela Express serve Baltimore's Penn Station, BWI Airport, New Carrollton, and Aberdeen along the Washington, D.C. to Boston Northeast Corridor. In addition, train service is provided to Rockville and Cumberland by Amtrak's Washington, D.C., to Chicago Capitol Limited.

The WMATA's Metrorail rapid transit and Metrobus local bus systems (the 2nd and 6th busiest in the nation of their respective modes) provide service in Montgomery and Prince George's counties and connect them to Washington, D.C., with the express Metrobus Route B30 serving BWI Airport. The Maryland Transit Administration (often abbreviated as "MTA Maryland"), a state agency part of the Maryland Department of Transportation also provides transit services within the state. Headquartered in Baltimore, MTA's transit services are largely focused on central Maryland, as well as some portions of the Eastern Shore and Southern MD. Baltimore's Light RailLink and Metro SubwayLink systems serve its densely populated inner-city and the surrounding suburbs. The MTA also serves the city and its suburbs with its local bus service (the 9th largest system in the nation). The MTA's Commuter Bus system provides express coach service on longer routes connecting Washington, D.C. and Baltimore to parts of Central and Southern MD as well as the Eastern Shore. The commuter rail service, known as MARC, operates three lines which all terminate at Washington Union Station and provide service to Baltimore's Penn and Camden stations, Perryville, Frederick, and Martinsburg, WV. In addition, many suburban counties operate local bus systems which connect to and complement the larger MTA and WMATA/Metro services.

The MTA will also administer the Purple Line, an under-construction light rail line that will connect the Maryland branches of the Red, Green/Yellow, and Orange lines of the Washington Metro, as well as offer transfers to all three lines of the MARC commuter rail system.[165][166]

Freight rail transport is handled principally by two Class I railroads, as well as several smaller regional and local carriers. CSX Transportation has more extensive trackage throughout the state, with 560 miles (900 km),[167] followed by Norfolk Southern Railway. Major rail yards are located in Baltimore and Cumberland,[167] with an intermodal terminal (rail, truck and marine) in Baltimore.[168]

Law and government

The government of Maryland is conducted according to the state constitution. The government of Maryland, like the other 49 state governments, has exclusive authority over matters that lie entirely within the state's borders, except as limited by the Constitution of the United States.

Power in Maryland is divided among three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial. The Maryland General Assembly is composed of the Maryland House of Delegates and the Maryland Senate. Maryland's governor is unique in the United States as the office is vested with significant authority in budgeting. The legislature may not increase the governor's proposed budget expenditures. Unlike many other states, significant autonomy is granted to many of Maryland's counties.

Most of the business of government is conducted in Annapolis, the state capital. Elections for governor and most statewide offices, as well as most county elections, are held in midterm-election years (even-numbered years not divisible by four).

The judicial branch of state government consists of one united District Court of Maryland that sits in every county and Baltimore City, as well as 24 Circuit Courts sitting in each County and Baltimore City, the latter being courts of general jurisdiction for all civil disputes over $30,000, all equitable jurisdiction and major criminal proceedings. The intermediate appellate court is known as the Court of Special Appeals and the state supreme court is the Court of Appeals. The appearance of the judges of the Maryland Court of Appeals is unique; Maryland is the only state whose judges wear red robes.[169]

Taxation

Maryland imposes five income tax brackets, ranging from 2 to 6.25 percent of personal income.[170] The city of Baltimore and Maryland's 23 counties levy local "piggyback" income taxes at rates between 1.25 and 3.2 percent of Maryland taxable income. Local officials set the rates and the revenue is returned to the local governments quarterly. The top income tax bracket of 9.45 percent is the fifth highest combined state and local income tax rates in the country, behind New York City's 11.35 percent, California's 10.3 percent, Rhode Island's 9.9 percent, and Vermont's 9.5 percent.[171]

Maryland's state sales tax is six percent.[172] All real property in Maryland is subject to the property tax.[173] Generally, properties that are owned and used by religious, charitable, or educational organizations or property owned by the federal, state or local governments are exempt.[173] Property tax rates vary widely.[173] No restrictions or limitations on property taxes are imposed by the state, meaning cities and counties can set tax rates at the level they deem necessary to fund governmental services.[173]

Elections

Since before the Civil War, Maryland's elections have been largely controlled by the Democrats, which account for 54.9% of all registered voters as of May 2017.[174]

State elections are dominated by Baltimore and the populous suburban counties bordering Washington, D.C. and Baltimore: Montgomery, Prince George's, Anne Arundel, and Baltimore counties. As of July 2017,[175] sixty-six percent of the state's population resides in these six jurisdictions, most of which contain large, traditionally Democratic Voting blocs: African Americans in Baltimore City and Prince George's, federal employees in Prince George's, Anne Arundel, and Montgomery, and postgraduates in Montgomery. The remainder of the state, particularly Western Maryland and the Eastern Shore, is more supportive of Republicans.[citation needed] One of Maryland's best known political figures is a Republican—former governor Spiro Agnew, who pled no contest to tax evasion and resigned in 1973.[176]

In 1980, Maryland was one of six states to vote for Jimmy Carter. In 1992, Bill Clinton fared better in Maryland than any other state except his home state of Arkansas. In 1996, Maryland was Clinton's sixth best; in 2000, Maryland ranked fourth for Gore; and in 2004, John Kerry showed his fifth-best performance in Maryland. In 2008, Barack Obama won the state's 10 electoral votes with 61.9 percent of the vote to John McCain's 36.5 percent.

In 2002, former Governor Robert Ehrlich was the first Republican to be elected to that office in four decades, and after one term lost his seat to Baltimore Mayor and Democrat Martin O'Malley. Ehrlich ran again for governor in 2010, losing again to O'Malley.

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment of Maryland[177] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 2,232,620 | 55.01% | |||

| Republican | 1,006,569 | 24.80% | |||

| Independents, unaffiliated, and other | 819,273 | 20.19% | |||

| Total | 4,058,462 | 100.00% | |||

The 2006 election brought no change in the pattern of Democratic dominance. After Democratic Senator Paul Sarbanes announced that he was retiring, Democratic Congressman Benjamin Cardin defeated Republican Lieutenant Governor Michael S. Steele, with 55 percent of the vote, against Steele's 44 percent.

While Republicans usually win more counties, by piling up large margins in the west and east, they are also usually swamped by the more densely populated and heavily Democratic Baltimore–Washington axis. In 2008, for instance, McCain won 17 counties to Obama's six; Obama also carried Baltimore City. While McCain won most of the western and eastern counties by margins of 2-to-1 or more, he was almost completely shut out in the larger counties surrounding Baltimore and Washington; every large county except Anne Arundel went for Obama.[178]

From 2007 to 2011, U.S. Congressman Steny Hoyer (MD-5), a Democrat, was elected as Majority Leader for the 110th Congress and 111th Congress of the House of Representatives, serving in that post again starting in 2019. In addition, Hoyer served as House Minority Whip from 2003 to 2006 and 2012 to 2018. His district covers parts of Anne Arundel and Prince George's counties, in addition to all of Charles, Calvert and St. Mary's counties in southern Maryland.[179]

In 2010, Republicans won control of most counties. The Democratic Party remained in control of eight county governments, including that of Baltimore.[180]

In 2014, Larry Hogan, a Republican, was elected Governor of Maryland.[181] Hogan is the second Republican to become the Governor of Maryland since Spiro Agnew, who resigned in 1969 to become vice president. In 2018, Hogan was re-elected to a second term of office.

LGBT rights and community

In February 2010, Attorney General Doug Gansler issued an opinion stating that Maryland law should honor same-sex marriages from out of state. At the time, the state Supreme Court wrote a decision upholding marriage discrimination.[133]

On March 1, 2012, Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley signed the freedom to marry bill into law after it passed in the state legislature. Immediately after, opponents of same-sex marriage began collecting signatures to overturn the law. The law was scheduled to face a referendum, as Question 6, in the November 2012 election.[133]

In May 2012, Maryland's Court of Appeals ruled that the state will recognize marriages of same-sex couples who married out-of-state, no matter the outcome of the November election.[133]

Voters voted 52% to 48% for Question 6 on November 6, 2012. Same-sex couples began marrying in Maryland on January 1, 2013.[133]

A large majority (57%) of Maryland voters said they would vote to uphold the freedom to marry at the ballot in November 2012, with 37% saying they would vote against marriage for all couples. This is consistent with a January 2011 Gonzales Research & Marketing Strategies poll showing 51% support for marriage in the state.[182]

Media

A well-known newspaper is The Baltimore Sun.

The most populous areas are served by either Baltimore or Washington, D.C. broadcast stations. The Eastern Shore is served primarily by broadcast media based around the Delmarva Peninsula; the northeastern section receives both Baltimore and Philadelphia stations. Garrett County, which is mountainous, is served by stations from Pittsburgh, and requires cable or satellite for reception. Maryland is served by statewide PBS member station Maryland Public Television (MPT).

Education

Primary and secondary education

Education Week ranked Maryland #1 in its nationwide 2009–2013 Quality Counts reports.[citation needed] The College Board's 9th Annual AP Report to the Nation also ranked Maryland first.[citation needed] Primary and secondary education in Maryland is overseen by the Maryland State Department of Education, which is headquartered in Baltimore.[183] The highest educational official in the state is the State Superintendent of Schools, who is appointed by the State Board of Education to a four-year term of office. The Maryland General Assembly has given the Superintendent and State Board autonomy to make educationally related decisions, limiting its influence on the day-to-day functions of public education. Each county and county-equivalent in Maryland has a local Board of Education charged with running the public schools in that particular jurisdiction.

The budget for education was $5.5 billion in 2009, representing about 40 percent of the state's general fund.[184]